by Nicole C. Woitowich, PhD

I am what you might stereotype as a “girly girl.” I love everything that comes in pink, I have seen the movie Legally Blonde more times than I would like to admit, and whatever Taylor Swift song is popular at the moment is probably my “jam.”

I am also a biochemist.

Are these things mutually exclusive? Do women need to hide their love for bold colors, high heels, and pop culture in order to be taken seriously as a scientist? Apparently so, according to many blogs and articles written by other female scientists. Their advice ranges from keeping makeup natural, to wearing dark colors to look more authoritative, or adding “soft touches” such as scarves if you must feel “feminine.”

The worst part is, their advice isn’t entirely wrong. A recent study by Dr. Sarah Banchefsky and colleagues at the University of Colorado Boulder asked participants to rank photos, unbeknownst to them of real scientists, on their gendered appearance (masculine or feminine) and career likelihood (scientist or early childhood educator). They found that the more feminine a woman appeared, the less likely she was deemed to be a scientist.

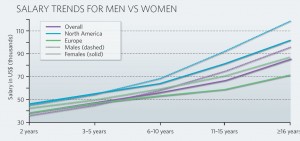

Together with the current climate in the scientific workforce where women are under-represented in leadership roles and tenured faculty, I almost understand why women would want to “tone it down,” and adopt the dress and social behaviors of their male peers.

Banchefsky, lead author of the study, provides some insight, “We all, to a certain degree, adapt and conform to fit into the environment around us and avoid having people ask questions or look at us askance. I think women do this to be taken seriously, to avoid being asked, ‘Are you really a scientist?’”

Furthermore, she adds, “…men serve as the power holders and gate-keepers in [STEM] fields, so women work hard to and want to be a part of their circle. Unfortunately, women’s assimilation reinforces the masculine culture in STEM.”

Hiding or limiting femininity may impart damaging consequences on young and aspiring scientists as well. According to Banchefsky, “If [young women] have in their mind that first, women aren’t typically in science, and when they are, they need to be gender-neutral or non-feminine - they may worry that they won’t be able to express part of who they are [through] their gender identity in a science field.”

“I think it’s important to highlight that it just doesn’t have to be this way,” Banchefsky states, and I completely agree.

To this end, I will continue to match my pink goggles to my outfit and wear pink nitrile gloves because it makes me feel more like “me.” So when young women visit the laboratory they can see that a scientist can be whomever she wants to be.

Source: Banchefsky et al., Sex Roles. 2016; Epub ahead of print.

Policy changes are necessary to decrease the death rate of pregnant women in developing countries. Research, according to Dr. Stacie E. Geller, does not end once scientists publish. The true battle is implementing that research to affect global change. Dr. Stacie E. Geller, Director of the Center for Research on Women and Gender at the University of Illinois at Chicago College of Medicine, puts research into practice by providing safe, affordable medication to pregnant women in developing countries. Dr. Geller spoke last week at a forum held at Northwestern University's Feinberg School of Medicine and presented her research on Postpartum Hemorrhaging (PPH) and its dangers to women in developing countries.

Policy changes are necessary to decrease the death rate of pregnant women in developing countries. Research, according to Dr. Stacie E. Geller, does not end once scientists publish. The true battle is implementing that research to affect global change. Dr. Stacie E. Geller, Director of the Center for Research on Women and Gender at the University of Illinois at Chicago College of Medicine, puts research into practice by providing safe, affordable medication to pregnant women in developing countries. Dr. Geller spoke last week at a forum held at Northwestern University's Feinberg School of Medicine and presented her research on Postpartum Hemorrhaging (PPH) and its dangers to women in developing countries. Northwestern University and the University of Chicago have launched the Chicago Collaboration for Women in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics, a three-year effort to enhance the recruitment and advancement of women faculty members in those fields.

Northwestern University and the University of Chicago have launched the Chicago Collaboration for Women in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics, a three-year effort to enhance the recruitment and advancement of women faculty members in those fields.

Several Northwestern researchers, including our own

Several Northwestern researchers, including our own