In celebration of Women's Heart Month, the Institute for Women's Health Research featured heart disease in women in its February E-newsletter. To view this free newsletter, click Heart Disease in Women Enewsletter.

In celebration of Women's Heart Month, the Institute for Women's Health Research featured heart disease in women in its February E-newsletter. To view this free newsletter, click Heart Disease in Women Enewsletter.

Women who report having high job strain have a 40 percent increased risk of cardiovascular disease, including heart attacks and the need for procedures to open blocked arteries, compared to those with low job strain, according to research presented at the American Heart Association's Scientific Sessions 2010.

Women who report having high job strain have a 40 percent increased risk of cardiovascular disease, including heart attacks and the need for procedures to open blocked arteries, compared to those with low job strain, according to research presented at the American Heart Association's Scientific Sessions 2010.

In addition, job insecurity -- fear of losing one's job -- was associated with risk factors for cardiovascular disease such as high blood pressure, increased cholesterol and excess body weight. However, it's not directly associated with heart attacks, stroke, invasive heart procedures or cardiovascular death, researchers said. Job strain, a form of psychological stress, is defined as having a demanding job, but little to no decision-making authority or opportunities to use one's creative or individual skills.

"Our study indicates that there are both immediate and long-term clinically documented cardiovascular health effects of job strain in women," said Michelle A. Albert, M.D., M.P.H., the study's senior author and associate physician at Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, Mass. "Your job can positively and negatively affect health, making it important to pay attention to the stresses of your job as part of your total health package."

Researchers analyzed job strain in 17,415 healthy women who participated in the landmark Women's Health Study. The women were primarily Caucasian health professionals, average age 57 who provided information about heart disease risk factors, job strain and job insecurity. They were followed for more than 10 years to track the development of cardiovascular disease. Researchers used a standard questionnaire to evaluate job strain and job insecurity with statements such as: "My job requires working very fast." "My job requires working very hard." "I am free from competing demands that others make."

The 40 percent higher risks for women who reported high job strain included heart attacks, ischemic strokes, coronary artery bypass surgery or balloon angioplasty and death. The increased risk of heart attack was about 88 percent, while the risk of bypass surgery or invasive procedure was about 43 percent.

"Women in jobs characterized by high demands and low control, as well as jobs with high demands but a high sense of control are at higher risk for heart disease long term," said Natalie Slopen, Sc.D., lead researcher and a postdoctoral research fellow at Harvard University Center on the Developing Child in Boston.

Previous research on the effects of job strain has focused on men and had a more restricted set of cardiovascular conditions. "From a public health perspective, it's crucial for employers, potential patients, as well as government and hospitals entities to monitor perceived employee job strain and initiate programs to alleviate job strain and perhaps positively impact prevention of heart disease," Albert said.

Source: American Heart Association (2010, November 15). ScienceDaily.

CHICAGO --- Is cardiovascular health in middle age and beyond a gift from your genes or is it earned by a healthy lifestyle and within your control?Two large studies from Northwestern Medicine confirm a healthy lifestyle has the biggest impact on cardiovascular health. One study shows the majority of people who adopted healthy lifestyle behaviors in young adulthood maintained a low cardiovascular risk profile in middle age. The five most important healthy behaviors are not smoking, low or no alcohol intake, weight control, physical activity and a healthy diet. The other study shows cardiovascular health is due primarily to lifestyle factors and healthy behavior, not heredity.

CHICAGO --- Is cardiovascular health in middle age and beyond a gift from your genes or is it earned by a healthy lifestyle and within your control?Two large studies from Northwestern Medicine confirm a healthy lifestyle has the biggest impact on cardiovascular health. One study shows the majority of people who adopted healthy lifestyle behaviors in young adulthood maintained a low cardiovascular risk profile in middle age. The five most important healthy behaviors are not smoking, low or no alcohol intake, weight control, physical activity and a healthy diet. The other study shows cardiovascular health is due primarily to lifestyle factors and healthy behavior, not heredity.

“Health behaviors can trump a lot of your genetics,” said Donald Lloyd-Jones, M.D., chair and professor of preventive medicine at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine and a staff cardiologist at Northwestern Memorial Hospital. “This research shows people have control over their heart health. The earlier they start making healthy choices, the more likely they are to maintain a low-risk profile for heart disease.”

Why Many Healthy Young Adults Become High Risk

The first Northwestern Medicine study investigated why most young adults, who have a low-risk profile for heart disease, often tip into the high-risk category by middle age with high blood pressure, high cholesterol and excess weight. The unhealthy shift is the result of lifestyle, the study found. More than half of the young adults who followed the five healthy lifestyle factors for 20 years were able to maintain their low-risk profile for heart disease though middle age. (The five healthy lifestyle factors are not smoking, low or no alcohol intake, weight control, physical activity and a healthy diet.)

“This means it is very important to adopt a healthy lifestyle at a younger age, because it will impact you later on,” said Kiang Liu, lead author of the study and a professor of preventive medicine at the Feinberg School.

There are big benefits to reaching middle age with a low-risk profile for heart disease. These individuals will live much longer, have a better quality of life and generate lower Medicare bills. A low-risk profile means low cholesterol, low blood pressure, no smoking, no diabetes, regular physical activity, a healthy diet and not overweight.

The study followed 2,336 black and white participants, ages 18 to 30 at baseline, for 20 years. Researchers tracked participants’ diet, physical activity, alcohol consumption, smoking, weight, blood pressure and glucose levels at the baseline year, year seven and year 20. The participants are part of the CARDIA (Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults) multi-center longitudinal study sponsored by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute.

After 20 years, the prevalence of a low-risk profile was 60 percent for participants who followed all five healthy lifestyle factors, 37 percent for four factors, 30 percent for three factors, 17 percent for two and 6 percent for one or zero. The results were similar for men only, women only, black only and white only.

“From a public health point of view, this shows we should put more emphasis on promoting a healthy lifestyle in young adulthood,” Liu said. “We need to educate and encourage younger people to do this now, so they’ll benefit when they get older.”

Tracking Three Generations of Families for Cardiovascular Health

The second Northwestern Medicine study examined three generations of families from the Framingham Heart Study to determine the heritability of cardiovascular health. Heritability includes a combination of genetic factors and the effects of a shared environment such as the types of foods that are served in a family. Only a small percentage of the United States population – 8 percent -- has ideal levels of all the risk factors for cardiovascular health at middle age.

The study found that only a small proportion of cardiovascular health is passed from parent to child; instead, it appears that the majority of cardiovascular health is due to lifestyle and healthy behaviors.

“What you do and how you live is going to have a larger impact on whether you are in ideal cardiovascular health than your genes or how you were raised,“ said Norrina Allen, the lead study author and a postdoctoral fellow in preventive medicine at the Feinberg School.

The Northwestern Medicine study looked at three generations of families including 7,535 people at age 40 and a separate group of 8,920 people at age 50. The goal was to see who was in ideal cardiovascular health at these two critical periods in middle age.

“We really need to encourage individuals to improve their behavior and lifestyle and create a public health environment so people can make healthy choices,” Lloyd-Jones said. “We need to make it possible for people to walk more and safely in their neighborhoods and buy fresh affordable fruit and vegetables in the local grocery store. We need physical activity back in schools, widely applied indoor smoking bans and reduced sodium content in the processed foods we eat. We also need to educate people to reduce their calorie intake. It’s a partnership between individuals making behavior changes but also public health changes that will improve the environment and allow people to make those healthy choices.”

Marla Paul is the health sciences editor. Contact her at marla-paul@northwestern.edu

In the largest human study to date on the topic, researchers have uncovered evidence of the possible influence of human sex hormones on the structure and function of the right ventricle (RV) of the heart.

The researchers found that in women receiving hormone therapy, higher estrogen levels were associated with higher RV ejection fraction (ejection refers to the amount of blood pumped out during a contraction; fraction refers to the residue left in the ventricle after the contraction) with each heart beat and lower RV end-systolic volume — both measures of the RV’s blood-pumping efficiency — but not in women who were not on hormone therapy, nor in men. Conversely, higher testosterone levels were associated with greater RV mass and larger volumes in men, but not in women, and DHEA, an androgen which improves survival in animal models of pulmonary hypertension, was associated with greater RV mass and volumes in women, similar to the findings with testosterone in men.

“This study highlights how little is known about the effects of sex hormones on RV function. It is critical from both research and clinical standpoints to begin to answer these questions,” said Steven Kawut, M.D., M.S., director of the Pulmonary Vascular Disease Program at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine in Philadelphia.

The study was published online ahead of the print edition of the American Thoracic Society’s American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine.

Study participants were part of The MESA-Right Ventricle Study (or MESA-RV), an extension of the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), a large, NHLBI-supported cohort focused on finding early signs of heart, lung and blood diseases before symptoms appear. Using blood samples and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the heart, researchers measured sex hormones and RV structure and function in 1957 men and 1738 post-menopausal women. Because the MESA population is ethnically mixed and covers a broad age range of apparently healthy people, the results may be widely applicable to the general U.S. population.

“One of the most interesting things about this research is that we are focusing on individuals without clinical cardiovascular disease so that we may learn about determinants of RV morphology before there is frank RV dysfunction, which is an end-stage complication of many heart and lung diseases,” said Dr. Kawut. “When we study people who already have RV failure from long-standing conditions, the horse has already left the barn. We are trying to assess markers that could one day help us identify and intervene in individuals at risk for RV dysfunction before they get really sick.”

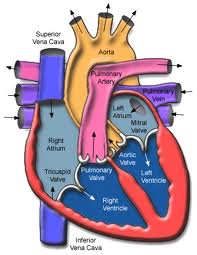

Because the RV plays a critical role in supplying blood to the lungs and the rest of the body, RV function is closely tied to clinical outcomes in many diseases where both the heart and lungs are involved, such as pulmonary hypertension, COPD and congestive heart failure. However, the RV is more difficult to study and image than the left ventricle and comparatively little is known about its structure and function and how to treat or prevent right heart failure.

Corey E. Ventetuolo, M.D., lead author of the study from Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, reported, “Our results have generated some interesting questions about RV response to the hormonal milieu. For example, the finding that higher levels of testosterone (and DHEA) were associated with greater RV mass would first appear to have adverse clinical consequences, since increasing cardiac mass is traditionally thought to be maladaptive. However, another study from MESA-RV has shown that higher levels of physical activity are also linked to greater RV mass, which would suggest an adaptive effect. So, whether the increased RV mass seen with higher hormone levels is helpful or harmful is not yet clear. The sex-specific nature of the associations we found was unexpected and reflect the complexity of the actions of sex hormones.”

Sex hormone levels could help explain a key paradox in pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), where the RV response is an important determinant of survival. While women are far more likely to develop PAH, they also have better RV function and may have a better survival than men. “It is possible that hormone balance could predispose them to developing PAH, but confer a protective benefit in terms of RV adaptation,” explained Dr. Kawut.

The ultimate goal would be strategies to treat or prevent RV failure in those at high risk.

Source: American Thoracic Society

What is Heart Disease?

Heart Disease is a general term used to describe various diseases and syndromes of the heart and blood vessels. Included in the definition are diseases such as coronary artery disease, heart arrhythmia, heart valve disease, heart failure, and congenital heart defects, among others.

Heart disease is the number one killer of both men and women worldwide, but may be prevented or treated with healthy lifestyle choices. The symptoms of heart disease vary dependent on the specific condition but include chest pain, shortness of breath, fluttering in the chest, swelling in the lower limbs, and fatigue. Symptoms of a myocardial infarction (or heart attack) tend to be different between men and women, with women experiencing more subtle symptoms such as fatigue, shortness of breath and nausea. Consequently, it may be more difficult for health professionals to diagnose and respond to a heart attack in a woman. In addition, recent research has shown that women suffer disproportionately than men from coronary artery disease in the small vessels (arterioles) as opposed to the larger arteries. This may further complicate diagnosis and treatment of heart disease in women.

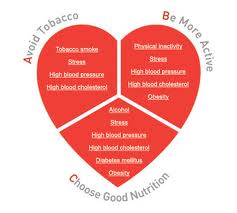

Causes of heart and cardiovascular disease include poor diet, little exercise, obesity, smoking, and high blood pressure, but may also be caused by congenital defects. A healthy diet and exercise along with maintenance of blood pressure, cholesterol, and stress may help reduce the risk of heart disease. Treatments for heart disease include lifestyle changes, medication, and in some cases surgery, and it is best treated when diagnosed early.

Resources at Northwestern for Heart Disease:

The Bluhm Cardiovascular Institute at Northwestern Memorial Hospital offers state-of-the-art treatment in all areas of cardiovascular care. Patients receive a comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach to treatment and prevention from physicians, nurses and other healthcare providers specializing in cardiology, cardiac surgery, vascular medicine and surgery, cardiovascular anesthesiology, cardiac behavioral medicine and radiology, among others. The Institute is comprised of six heart health centers for atrial fibrulation, coronary disease, heart failure, heart valve disease, vascular disease, and women’s cardiovascular health. The Women’s Cardiovascular Health Center offers treatment specifically designed for women, tailoring treatment plans to optimize their specific cardiovascular needs. The Center is also committed to promoting women’s awareness of cardiovascular health, highlighting the differences in symptoms and risk factors for women.

For more information call: (866) 662-8467 (toll free)

Northwestern Physicians/Researchers specializing in Heart Disease:

Researchers at the Feinberg Cardiovascular Research Institute are committed to exploring complex problems in cardiovascular research including molecular, cellular, stem cell and imaging technology research. Investigators at the Institute work in areas of basic science and clinical research. The innovative program in Cardiovascular Regenerative Medicine seeks out new ways of growing new cardiac tissue as opposed to improving function of damaged tissues. The program provides researchers with the means to bring basic science research into use in clinical trials. Led by Dr. Douglas Losordo, MD, clinical trials are being conducted for treatment in the areas of coronary artery disease, heart failure, and vascular disease.

For more information visit: http://www.fcvri.northwestern.edu/index.html

IWHR Highlighted Researcher

Dr. Mercedes Carnethon is an Assistant Professor of Preventative Medicine at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine. She earned her PhD in Epidemiology from the University of North Carolina in 2000 and joined the faculty of Northwestern in 2002. Her research interests include the role of the nervous system on cardiovascular disease (CVD), the relationship between fitness and cardiovascular health and the effects of sleep on the risk for CVD. She is a member of several professional societies including the American College of Epidemiology and the American Heart Association. Most recently, Dr. Carnethon has initiated a study to evaluate how sleep duration might affect a patient’s risk for cardiovascular disease. Previous studies have evaluated patients with major sleep disturbances, such as sleep apnea, or have used sleep deprivation to evaluate the relationship. Dr. Carnethon’s study will more closely mirror how women and men sleep during a normal week, and compare their sleep duration to indicators of their cardiovascular health. The study hopes to justify the recommendations for total amount of sleep that an adult might need to maintain his or her heart health.

Photo: The Heart Truth Campaign

Upcoming Public Events:

NMH Annual Cardiovascular Symposium: Heart Health – What Smart Women Need to Know, February 24, 2010, Prentice Women’s Hospital

Don't Forget - National Wear Red Day® is February 5th!

Health.com published an article today that summarizes the findings of a recent study on menopause and cholesterol that shows women's cholesterol levels increase at the time of menopause. The study's abstract can be found here, at the Journal of the American College of Cardiology site.

Image: heart-valve-surgery.com

It isn't news that cholesterol and other risks of heart disease increase as women age, but the study wanted to determine if the cholesterol increase was due to simple aging, or more specifically related to menopause. They found that within two years of a woman's last period, her LDL cholesterol (so-called bad cholesterol) jumps about 10 points. This increase may be small, but if a woman already has elevated cholesterol, it could be problematic. Additionally, since other risk factors for heart disease increase with age, this increase in cholesterol could team with other cardio-related age affects to create an increased risk of heart problems. The study authors suggest that peri-menopausal women take this news under advisement and become even more vigilant about their diet and exercise routines.

This study is not only interesting because of the findings, but also because of the methodology they employed; the researchers used self-reported data from a national health registry to conduct their study. The Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN) is very akin to our state based registry, the Illinois Women's Health Registry (if you live in Illinois, go join!). Analysis of these surveys and normal everyday women who participated pulled out this very interesting finding. It's quite clear that this is a great example of why gender-based research is so necessary, study of cholesterol rates in an all-male study group would never have discovered this connection! Finally, the study concluded that the link between increased cholesterol and menopause was true for most ethnicities...because they included women from many ethnicities! It's amazing how much more we learn when diverse participants are used for clinical research studies!

Photo: Lamis Eli, Sarah Kiesewetter

A study was recently published online in the journal Circulation, the journal of the American Heart Association, showing that optimistic women are less likely to suffer from, or die of, heart disease. The study is actually really fascinating (the article abstract and the downloadable entire article can be found here.)

I think this particular study highlights some important points:

1. The study participants are very much like the group that we are trying to collect through the Illinois Women's Health Registry (if you’re an Illinois resident, go join!). They were women in the government-funded Women's Health Initiative, and the sheer number and racial diversity of participants allowed researchers to make new connections, simply by following the women’s health progress for a couple of years and administering very short questionnaires. It’s amazing what we can do when we all participate in these kind of registries!

2. I think the connection between mental well-being and physical health is really starting to become a key research topic and is likely changing the way patients are treated. As an admitted pessimistic cynic, I really do understand that those stress headaches and upset stomachs are taking their toll, and can be largely under my control. That’s pretty empowering, even for a pessimist.

3. It’s a great example of the benefits of studying several groups of people in scientific studies. The researchers found several statistical differences between the white and black women studied (the disparity in health outcomes between optimists and pessimists was much more striking in the black women studied, for example.) These differences would have been missed if men or white women were allowed to portray some standard of the everyperson.

So go read up! The questions used to classify a person as optimistic or hostile and cynical are particularly amusing, such as having to answer true or false to “ I have often had to take orders from someone who did not know as much as I did,” or “It is safer to trust nobody.” I know I’ll be thinking twice about those negative thoughts about my higher-ups!