What is Heart Disease?

Heart Disease is a general term used to describe various diseases and syndromes of the heart and blood vessels. Included in the definition are diseases such as coronary artery disease, heart arrhythmia, heart valve disease, heart failure, and congenital heart defects, among others.

Heart disease is the number one killer of both men and women worldwide, but may be prevented or treated with healthy lifestyle choices. The symptoms of heart disease vary dependent on the specific condition but include chest pain, shortness of breath, fluttering in the chest, swelling in the lower limbs, and fatigue. Symptoms of a myocardial infarction (or heart attack) tend to be different between men and women, with women experiencing more subtle symptoms such as fatigue, shortness of breath and nausea. Consequently, it may be more difficult for health professionals to diagnose and respond to a heart attack in a woman. In addition, recent research has shown that women suffer disproportionately than men from coronary artery disease in the small vessels (arterioles) as opposed to the larger arteries. This may further complicate diagnosis and treatment of heart disease in women.

Causes of heart and cardiovascular disease include poor diet, little exercise, obesity, smoking, and high blood pressure, but may also be caused by congenital defects. A healthy diet and exercise along with maintenance of blood pressure, cholesterol, and stress may help reduce the risk of heart disease. Treatments for heart disease include lifestyle changes, medication, and in some cases surgery, and it is best treated when diagnosed early.

Resources at Northwestern for Heart Disease:

The Bluhm Cardiovascular Institute at Northwestern Memorial Hospital offers state-of-the-art treatment in all areas of cardiovascular care. Patients receive a comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach to treatment and prevention from physicians, nurses and other healthcare providers specializing in cardiology, cardiac surgery, vascular medicine and surgery, cardiovascular anesthesiology, cardiac behavioral medicine and radiology, among others. The Institute is comprised of six heart health centers for atrial fibrulation, coronary disease, heart failure, heart valve disease, vascular disease, and women’s cardiovascular health. The Women’s Cardiovascular Health Center offers treatment specifically designed for women, tailoring treatment plans to optimize their specific cardiovascular needs. The Center is also committed to promoting women’s awareness of cardiovascular health, highlighting the differences in symptoms and risk factors for women.

For more information call: (866) 662-8467 (toll free)

Northwestern Physicians/Researchers specializing in Heart Disease:

Researchers at the Feinberg Cardiovascular Research Institute are committed to exploring complex problems in cardiovascular research including molecular, cellular, stem cell and imaging technology research. Investigators at the Institute work in areas of basic science and clinical research. The innovative program in Cardiovascular Regenerative Medicine seeks out new ways of growing new cardiac tissue as opposed to improving function of damaged tissues. The program provides researchers with the means to bring basic science research into use in clinical trials. Led by Dr. Douglas Losordo, MD, clinical trials are being conducted for treatment in the areas of coronary artery disease, heart failure, and vascular disease.

For more information visit: http://www.fcvri.northwestern.edu/index.html

IWHR Highlighted Researcher

Dr. Mercedes Carnethon is an Assistant Professor of Preventative Medicine at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine. She earned her PhD in Epidemiology from the University of North Carolina in 2000 and joined the faculty of Northwestern in 2002. Her research interests include the role of the nervous system on cardiovascular disease (CVD), the relationship between fitness and cardiovascular health and the effects of sleep on the risk for CVD. She is a member of several professional societies including the American College of Epidemiology and the American Heart Association. Most recently, Dr. Carnethon has initiated a study to evaluate how sleep duration might affect a patient’s risk for cardiovascular disease. Previous studies have evaluated patients with major sleep disturbances, such as sleep apnea, or have used sleep deprivation to evaluate the relationship. Dr. Carnethon’s study will more closely mirror how women and men sleep during a normal week, and compare their sleep duration to indicators of their cardiovascular health. The study hopes to justify the recommendations for total amount of sleep that an adult might need to maintain his or her heart health.

Photo: The Heart Truth Campaign

Upcoming Public Events:

NMH Annual Cardiovascular Symposium: Heart Health – What Smart Women Need to Know, February 24, 2010, Prentice Women’s Hospital

Don't Forget - National Wear Red Day® is February 5th!

Women with the most serious type of angina are three times as likely as men with the same condition to develop severe coronary artery disease (CAD), researchers have found.

Women with the most serious type of angina are three times as likely as men with the same condition to develop severe coronary artery disease (CAD), researchers have found.

Middle-aged and elderly Swedish women who regularly ate a small amount of chocolate had lower risks of heart failure risks, in a study reported in Circulation: Heart Failure, a journal of the American Heart Association. The nine-year study, conducted among 31,823 middle-aged and elderly Swedish women, looked at the relationship of the amount of high-quality chocolate the women ate, compared to their risk for heart failure. The quality of chocolate consumed by the women had a higher density cocoa content somewhat like dark chocolate by American standards. In this study, researchers found:

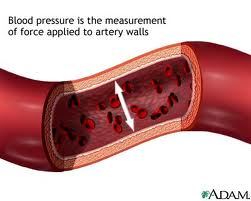

Middle-aged and elderly Swedish women who regularly ate a small amount of chocolate had lower risks of heart failure risks, in a study reported in Circulation: Heart Failure, a journal of the American Heart Association. The nine-year study, conducted among 31,823 middle-aged and elderly Swedish women, looked at the relationship of the amount of high-quality chocolate the women ate, compared to their risk for heart failure. The quality of chocolate consumed by the women had a higher density cocoa content somewhat like dark chocolate by American standards. In this study, researchers found: Postmenopausal women have an increased risk of hypertension (high blood pressure), and among older adults, more women than men have hypertension. As with many other health issues, hypertension research has been conducted predominately in males, and little is known about how women's bodies manage blood flow. Research conducted by Heidi A. Kluess at the University of Arkansas is focusing on a better understanding of hypertension in women by using a new technique to examine the release of a neurotransmitter in small blood vessels.

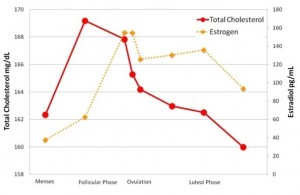

Postmenopausal women have an increased risk of hypertension (high blood pressure), and among older adults, more women than men have hypertension. As with many other health issues, hypertension research has been conducted predominately in males, and little is known about how women's bodies manage blood flow. Research conducted by Heidi A. Kluess at the University of Arkansas is focusing on a better understanding of hypertension in women by using a new technique to examine the release of a neurotransmitter in small blood vessels. Women's cholesterol levels vary with phase of menstrual cycle

Women's cholesterol levels vary with phase of menstrual cycle Women who measure their peak heart rates for exercise will need to do some new math, as will physicians giving stress tests to patients. A new formula based on a large study from Northwestern Medicine provides a more accurate estimate of the peak heart rate a healthy woman should attain during exercise. It also will more accurately predict the risk of heart-related death during a stress test.

Women who measure their peak heart rates for exercise will need to do some new math, as will physicians giving stress tests to patients. A new formula based on a large study from Northwestern Medicine provides a more accurate estimate of the peak heart rate a healthy woman should attain during exercise. It also will more accurately predict the risk of heart-related death during a stress test. A recent article by Appel and Anderson in the

A recent article by Appel and Anderson in the