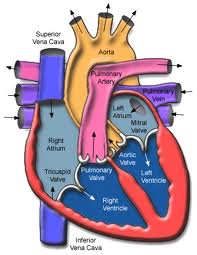

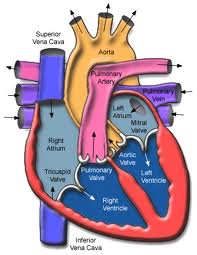

In the largest human study to date on the topic, researchers have uncovered evidence of the possible influence of human sex hormones on the structure and function of the right ventricle (RV) of the heart.

The researchers found that in women receiving hormone therapy, higher estrogen levels were associated with higher RV ejection fraction (ejection refers to the amount of blood pumped out during a contraction; fraction refers to the residue left in the ventricle after the contraction) with each heart beat and lower RV end-systolic volume — both measures of the RV’s blood-pumping efficiency — but not in women who were not on hormone therapy, nor in men. Conversely, higher testosterone levels were associated with greater RV mass and larger volumes in men, but not in women, and DHEA, an androgen which improves survival in animal models of pulmonary hypertension, was associated with greater RV mass and volumes in women, similar to the findings with testosterone in men.

“This study highlights how little is known about the effects of sex hormones on RV function. It is critical from both research and clinical standpoints to begin to answer these questions,” said Steven Kawut, M.D., M.S., director of the Pulmonary Vascular Disease Program at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine in Philadelphia.

The study was published online ahead of the print edition of the American Thoracic Society’s American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine.

Study participants were part of The MESA-Right Ventricle Study (or MESA-RV), an extension of the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), a large, NHLBI-supported cohort focused on finding early signs of heart, lung and blood diseases before symptoms appear. Using blood samples and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the heart, researchers measured sex hormones and RV structure and function in 1957 men and 1738 post-menopausal women. Because the MESA population is ethnically mixed and covers a broad age range of apparently healthy people, the results may be widely applicable to the general U.S. population.

“One of the most interesting things about this research is that we are focusing on individuals without clinical cardiovascular disease so that we may learn about determinants of RV morphology before there is frank RV dysfunction, which is an end-stage complication of many heart and lung diseases,” said Dr. Kawut. “When we study people who already have RV failure from long-standing conditions, the horse has already left the barn. We are trying to assess markers that could one day help us identify and intervene in individuals at risk for RV dysfunction before they get really sick.”

Because the RV plays a critical role in supplying blood to the lungs and the rest of the body, RV function is closely tied to clinical outcomes in many diseases where both the heart and lungs are involved, such as pulmonary hypertension, COPD and congestive heart failure. However, the RV is more difficult to study and image than the left ventricle and comparatively little is known about its structure and function and how to treat or prevent right heart failure.

Corey E. Ventetuolo, M.D., lead author of the study from Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, reported, “Our results have generated some interesting questions about RV response to the hormonal milieu. For example, the finding that higher levels of testosterone (and DHEA) were associated with greater RV mass would first appear to have adverse clinical consequences, since increasing cardiac mass is traditionally thought to be maladaptive. However, another study from MESA-RV has shown that higher levels of physical activity are also linked to greater RV mass, which would suggest an adaptive effect. So, whether the increased RV mass seen with higher hormone levels is helpful or harmful is not yet clear. The sex-specific nature of the associations we found was unexpected and reflect the complexity of the actions of sex hormones.”

Sex hormone levels could help explain a key paradox in pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), where the RV response is an important determinant of survival. While women are far more likely to develop PAH, they also have better RV function and may have a better survival than men. “It is possible that hormone balance could predispose them to developing PAH, but confer a protective benefit in terms of RV adaptation,” explained Dr. Kawut.

The ultimate goal would be strategies to treat or prevent RV failure in those at high risk.

Source: American Thoracic Society

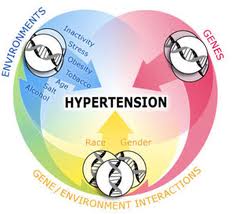

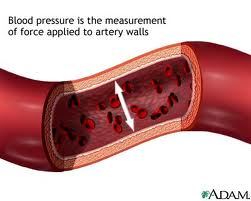

May Is National High Blood Pressure Education Month, and nearly one in three adults in the United States has high blood pressure, also called hypertension. High blood pressure is dangerous because it increases the risk of stroke, heart attack, heart failure, kidney failure, death.

May Is National High Blood Pressure Education Month, and nearly one in three adults in the United States has high blood pressure, also called hypertension. High blood pressure is dangerous because it increases the risk of stroke, heart attack, heart failure, kidney failure, death.

New research shows that women with high blood pressure during pregnancy may be at higher risk of having troublesome menopausal symptoms in the future. A research study from the Netherlands examined the relationship between hypertensive diseases and hot flashes and night sweats.

New research shows that women with high blood pressure during pregnancy may be at higher risk of having troublesome menopausal symptoms in the future. A research study from the Netherlands examined the relationship between hypertensive diseases and hot flashes and night sweats. In one of the largest genomic studies ever, an international research consortium identified 29 genetic variations that influence blood pressure. More than half of these variants were previously unknown. The findings provide insights into the biology of blood pressure and may lead to new therapeutic strategies.

In one of the largest genomic studies ever, an international research consortium identified 29 genetic variations that influence blood pressure. More than half of these variants were previously unknown. The findings provide insights into the biology of blood pressure and may lead to new therapeutic strategies. Women who tend to have high blood pressure (HBP) should be particularly vigilant if they are on oral contraceptives, are pregnant, or on hormone replacement therapy.

Women who tend to have high blood pressure (HBP) should be particularly vigilant if they are on oral contraceptives, are pregnant, or on hormone replacement therapy.

Postmenopausal women have an increased risk of hypertension (high blood pressure), and among older adults, more women than men have hypertension. As with many other health issues, hypertension research has been conducted predominately in males, and little is known about how women's bodies manage blood flow. Research conducted by Heidi A. Kluess at the University of Arkansas is focusing on a better understanding of hypertension in women by using a new technique to examine the release of a neurotransmitter in small blood vessels.

Postmenopausal women have an increased risk of hypertension (high blood pressure), and among older adults, more women than men have hypertension. As with many other health issues, hypertension research has been conducted predominately in males, and little is known about how women's bodies manage blood flow. Research conducted by Heidi A. Kluess at the University of Arkansas is focusing on a better understanding of hypertension in women by using a new technique to examine the release of a neurotransmitter in small blood vessels.