On Monday, The Scientist printed a valuable article linking to a TED video and a new book entitled Living Color by Nina Jablonski. The video and book delve into the importance of skin color and types for health and social well-being.

On Monday, The Scientist printed a valuable article linking to a TED video and a new book entitled Living Color by Nina Jablonski. The video and book delve into the importance of skin color and types for health and social well-being.

To me, there are three points of greatest value: 1) that as humans, our personal melanin and intake of ultraviolet radiation (UVR) are vitally important to our individual health, 2) that as migration and evolution has occurred our pigmentation gene is exceptionally labile, and 3) that skin pigmentation and our individual variations are not discussed nearly enough in our society.

Although I am an advocate for more open, honest dialogue about the significant role race has in this country, this argument for better quality health is different. We need to begin also addressing what pigmentation means for the individual and how women have varying skin needs. This message is not about Black, White, Asian, Latino, or any other socially constructed label for race or ethnicity, this is about individual health concerns.

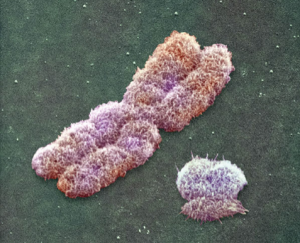

As the author correctly explains, the MC1R gene, which is the gene predominantly responsible for pigmentation, has little variation in African people. Those with darker (or more melanin-rich) skin have a “built-in defense” against harmful ultraviolet radiation, is often ideal for health and normal cell reproduction. However, as humans migrated and evolved there was a depigmentation of skin, leading to lightly pigmented (or melanin-poor) peoples. This mismatch of genetic predisposition and solar regimes can mean very different things for a woman’s health.

For example, Nina Jablonski asserts that, “People of Northern European ancestry, for instance, living in Florida or Australia confront intense UVR conditions with pale, melanin-poor skin and suffer from sunburns, high rates of skin cancer, and accelerated skin aging. People of central African or southern Indian ancestry living in Wisconsin or Wales face low and highly seasonal UVR conditions with exquisitely sun-protected skin and suffer from vitamin D deficiencies as a result.”

Ladies, knowing your body also means knowing the health risks and benefits associated with your skin. Remember, your skin is the largest organ in your body, talk to your health care providers and keep yourself safe!