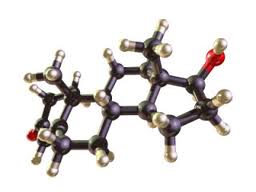

New research is surfacing that links anesthesia to inhibited cognitive developments in children under four. Significant brain development occurs in young children at this time, and ketamine—a common anesthetic—has been shown to affect the brain’s learning ability. Studies began back in 2003 when Merle Paule, Ph.D., director of the Division of Neurotoxicology at the FDA’s National Center for Toxicological Research, began observing the effects of ketamine on young rhesus monkeys, since this species closely resembles humans in physiology and behavior. While the ketamine-exposed monkeys performed cognitive experiments less accurately than the control group, the affect of ketamine on human children requires further research.

New research is surfacing that links anesthesia to inhibited cognitive developments in children under four. Significant brain development occurs in young children at this time, and ketamine—a common anesthetic—has been shown to affect the brain’s learning ability. Studies began back in 2003 when Merle Paule, Ph.D., director of the Division of Neurotoxicology at the FDA’s National Center for Toxicological Research, began observing the effects of ketamine on young rhesus monkeys, since this species closely resembles humans in physiology and behavior. While the ketamine-exposed monkeys performed cognitive experiments less accurately than the control group, the affect of ketamine on human children requires further research.

Interest in this area grew so much that, in 2010, the FDA and the International Anesthesia Research Society founded an initiative called Strategies for Mitigating Anesthesia-Related neuroToxicity in Tots, or “SmartTots” for short. Director of Anesthesia, Analgesia and Addiction Products at FDA, Bob Rappaport, M.D. said, “Our hope is that research funded through SmartTots will help us design the safest anesthetic regimens possible.” SmartTots continues to advocate for research that can protect the millions of children who receive anesthesia each year.

Supplemental studies are necessary to understand whether all forms of anesthetics elicit similar deficits as ketamine, and, if so, how long these deficits last. Columbia University and the University of Iowa are currently exploring the effects of anesthesia on infant brain development and cognitive and language ability, thanks to the funding from SmartTots. Until more conclusive data is published, parents are urged to work closely with their child’s clinicians in weighing all options and risks before exposing young children to anesthesia.

Click here to read more on this issue.